Pop Bibliography

Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Harry Potter*. The Elder Scrolls. Star Wars. Dungeons and Dragons. TRON: Legacy. Magic: The Gathering. None of these media properties are ostensibly about old books, but nevertheless feature them as mood-setting backgrounds, key props, and markers of an ambiguously-defined past. And they are not isolated examples: pull up almost any fantasy game on Steam, queue up your favorite historical drama on Netflix, or get cozy with an isekai manga, and you are likely to encounter “old” books as concepts, tools, and/or scene-setting ambiance.

Dragon Spell, by Jan Patrik Kransy

But why these books? And what messages are they conveying? For book historians and those in rare book related fields, the objects one frequently encounters in fiction are curious hybrids of extant historic book structures and aesthetics. These mashed-together physical attributes from different times and places create something that looks like an “old” book to a general audience, without much engagement with the functionality or significance of said attributes. Bookish settings cultivate “identity derived from a physical nearness to books” (Pressman, 10), and foster a fetishistic nostalgia for “a time when books smelled” (102). But where did the visual vocabulary for these “old” books originate, and what can it tell us about the popular understanding of the book as an object? This is what Pop Bibliography helps to illuminate: both the anachronistic, chimera-like book objects and the popular reaction to the visual language of “old” books.

Books being used as visual shorthand for the general idea of learned-ness is not a new concept – strolling through any portrait gallery will yield a host of historical examples of upper class people explicitly using books and libraries as props to communicate the image of an intellectual. “Books are more than repositories of text; they are icons of knowledge,” notes Jessica Pressman (32). And Brian Cummings, in his discussion of the book as a symbol observes that, more than other objects, old books are “felt to embody not only a physical memory but also a record of past thoughts [...], of transforming what appears to be purely immaterial and conceptual into something with a concrete form.” (93)

But considering the general populace’s unfamiliarity with old books, media properties that feature such objects are using them as symbols of symbols; they are deep in skeuomorph territory, with their physical attributes serving no purpose other than to evoke Pastness. Pastness – defined by Cornelius Holtorf as the “particular appearance [of an object or place] corresponding to the past in your imagination” (27) – is the linchpin of Pop Bibliography. It’s not rare books, it’s the thing you think you remember about rare books.

Pop Bibliography draws from both the ideas of Pop Art and Megan L Cook’s Dirtbag Medievalism. It’s not a hard science; it’s more of a vibe. That being said, here are some of Pop Bibliography’s hallmarks:

IT IS COMMERCIAL. Pop Bibliography’s primary function is marketability. Books in media look cool and interesting because someone wants them to look cool and interesting, in order to appeal to a variety of audiences and generate a profit. And the tastes of audiences are prone to change: this can be seen by tracking the visual development of books as featured in long-lived franchises such as Magic: The Gathering. Players now expect a certain level of complexity in Magic’s card illustrations, and by extension, the books that pop up in them; the art directors are happy to oblige. Pop Bibliography plays very well with Pressman’s Bookishness to cultivate not just an identity as a reader, but a reader that values the past.

Two cards from Magic: The Gathering, dating from 1993 (left) and 2023 (right).

IT IS (usually) NOT THE CENTER OF ATTENTION. It can be seen in the background of films in which books are never addressed or discussed; it can be seen as the constant tool of the video game mage, or as the key MacGuffin that will resolve a fantastic plot. It can even be observed in books humanized to various degrees who act as supporting characters. But Pop Bibliography is almost never the main character. (I am purposely adding this “almost never” caveat here; I welcome any media examples where an Old Book is the protagonist, outside Swift’s Battle of the Books [and even here, the books are so humanized that they lose their codicological attributes].) This is by design: Bookishness in the Pressman sense is particularly effective when the audience has an avatar through which they can envision themselves in a fantastic environment, and that they can identify with in the real world. The number of researchers and heritage professionals who have posted the gif of a harried Gandalf rifling through old books with the caption “me today in the reading room” is very far from zero.

Gandalf doing research from The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

IT IS DIFFUSED, A DREAM OF A DREAM. Umberto Eco describes a variety of ways of “dreaming” of the medieval period, outlining ten little Middle ages. His definition of dream in this formative piece aligns more closely with an interest, or a striving for, or a hope; the dream inherent to Pop Bibliography instead denotes an unconscious state where the wanderings of one’s mind fade in and out of comprehension, concrete shapes and ideas flowing around and through each other with no concern for boundaries: conceptual, physical, or temporal. Pop Bibliography is the image of what you think you remember about books.

IT IS A BLEND. This diffusion and blurring of borders generates a sort of book stew for designers to dip into. This stew is full of chopped-up, decontextualized physical attributes in different amounts. For example, a spoonful will frequently contain a leather binding, conspicuous wear and tear, and calligraphic contents, but sometimes you wind up with illumination from Arabic tradition or a 19th century pictorial cloth binding. The ending credits of the 2023 Dungeons and Dragons film is a spectacular example of this blending. The main ingredient is a gradient of western late medieval illumination into Persian illumination; it hops from the manuscript to print in the visible bite of the figure combined with a bestiary-inspired illumination, and then to the late 19th century in the form of this style of moveable book. And a second example: though the 1994 movie The Pagemaster is very Bookish in the Pressman sense, it does not dabble much in Pop Bibliography. However its title sequence, composed of aesthetic nods to manuscripts and early printing, is.

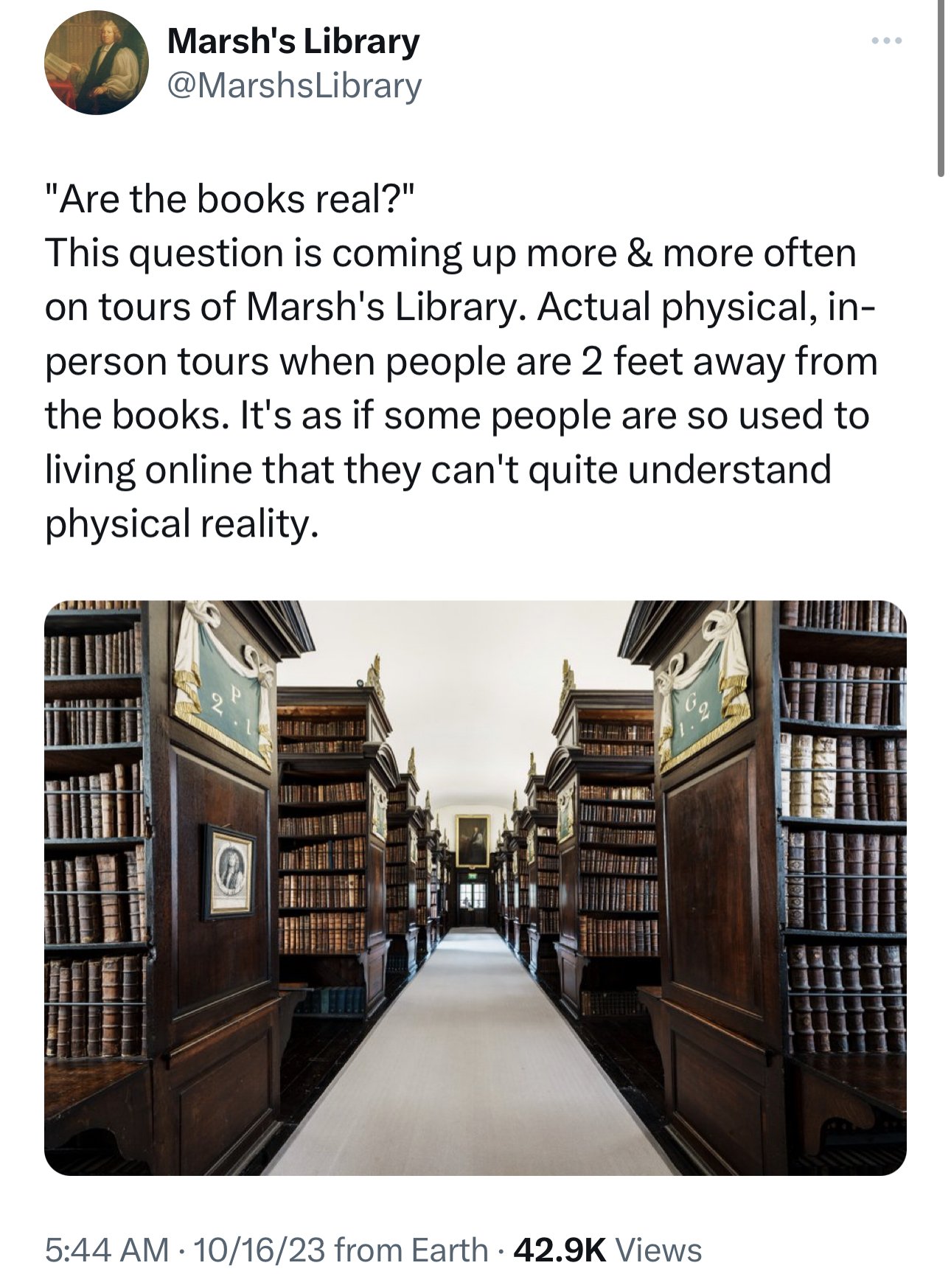

Are the books real? It’s complicated…

IT IS FETISHISTIC. It exploits the remoteness of the general public from “real” old books to create desire. But this idea did not spring from the void – it is rooted in an older cultural concept. The historic unattainability of books contributes to persistent ideas of their mystique – the sense that certain kinds of books are perpetually out of reach is a remnant of the pre-mid-19th century period when the vast majority of books were far outside the price range of the common person. The role that highly embellished books have traditionally played in religious contexts also lends them a sense of sacred untouchability.

This mentality is perpetuated in the 21st century by misconceptions about the accessibility of special collections libraries and the high prices of many medieval books on the market. At the same time, books as a commodity are so ubiquitous today that their form and function are generally taken for granted. But the medieval manuscripts, early modern herbals, and massive religious works sporting bars and chains that inspire the depiction of books in fictional properties are no less real than the books on an average shelf. This recent hand-wringing tweet from Marsh’s Library in Ireland is an anecdote of how the fetish aspect of Pop Bibliography manifests in the general public, though the despairing tone shows a missed opportunity to engage on the visitor’s level.

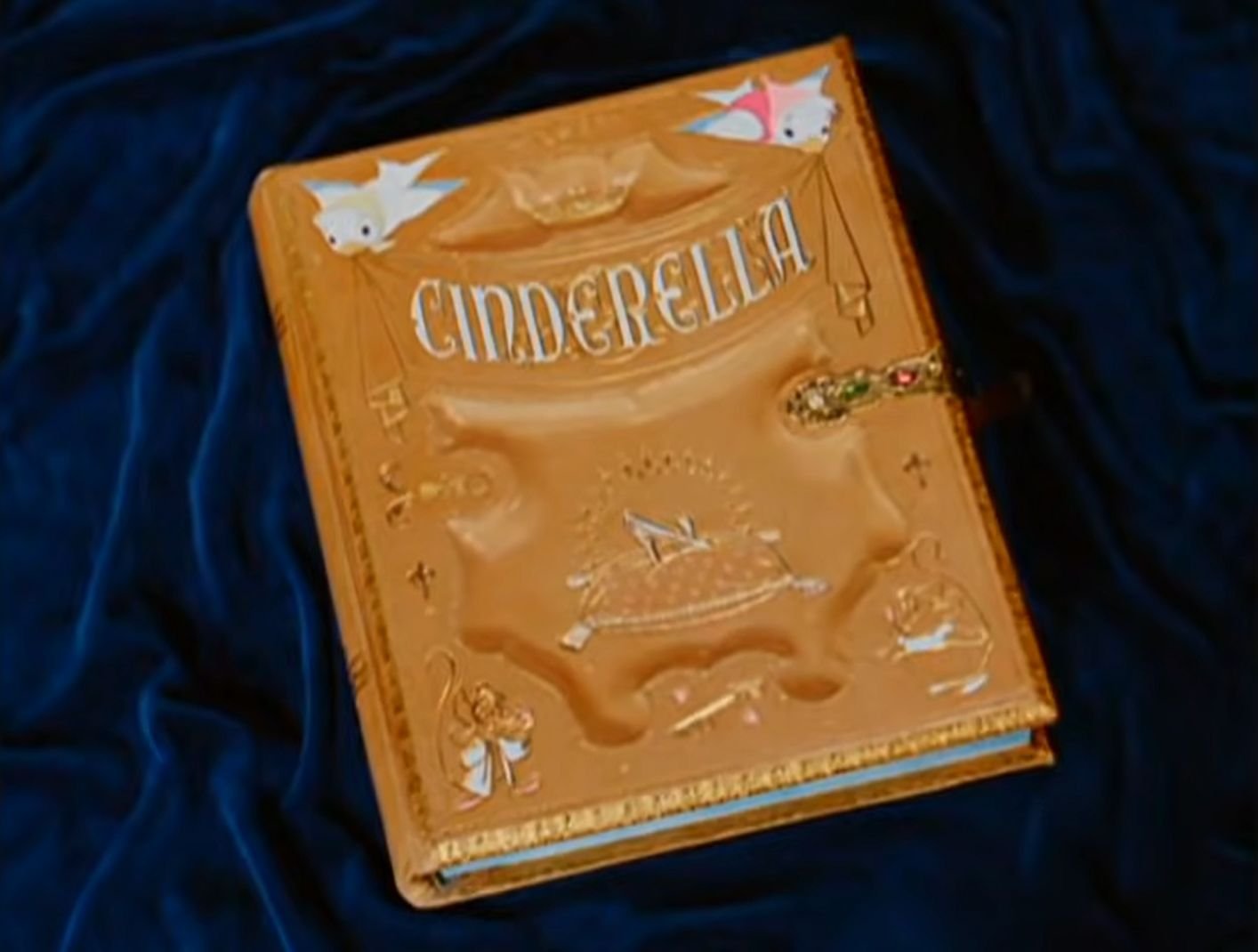

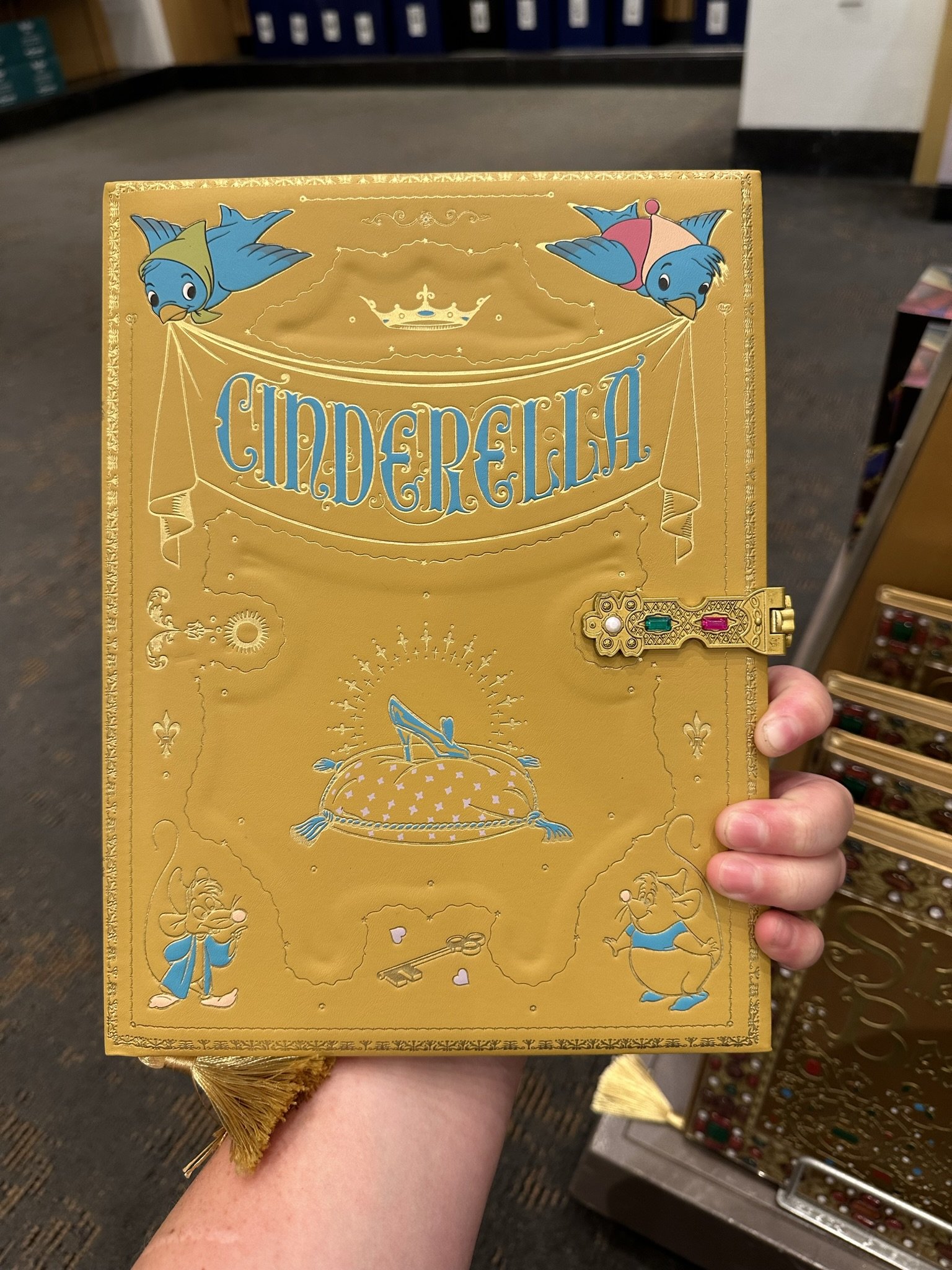

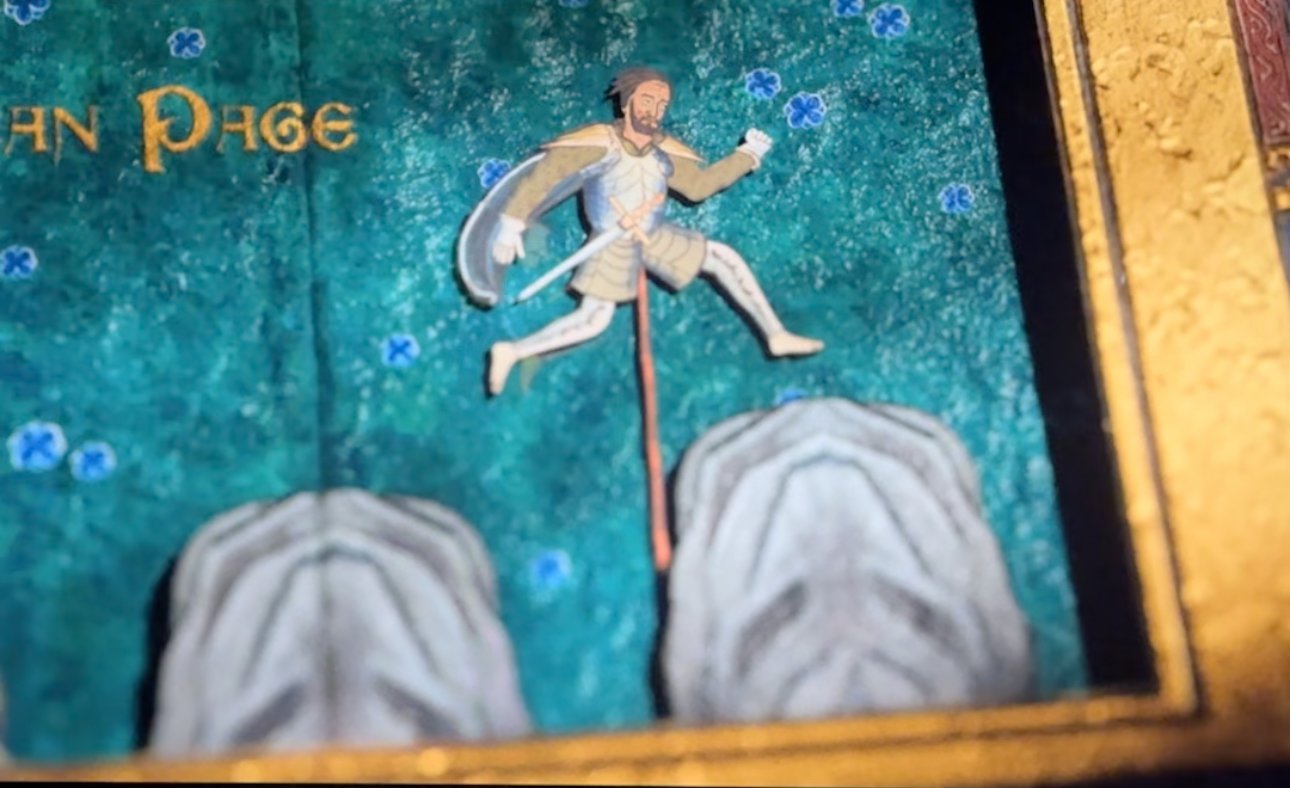

IT STRAYS INTO THE REAL WORLD. Circling back to its commercial nature, Pop Bibliography is a prime candidate for merchandising. These embellished blank books for sale in a shop in Disney World are replicas of the pseudo-medieval story books that feature in the opening sequences of Disney’s Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella. I personally own a plastic book safe that is a replica of a key item from the Cardcaptor Sakura anime. However, Paper Blanks journals, which are notebook reproductions of extant rare books and manuscripts, are not Pop Bibliography.

IT IS NOT REAL, BUT IT DOESN’T MIND IF IT’S TAKEN AS SUCH. Facsimiles are not Pop Bibliography; in order to fit the Pop Bibliography mold, someone has to have gotten kind of weird with it. Properties such as the Ascendance of a Bookworm anime, in which the development of the codex form and moveable type printing in a fantasy setting are a key plot point, dance this line. While most people wouldn’t look at a wizardly tome in Dr. Strange’s library and say “this is a historical object that actually exists in the real world,” they very easily could get that sense from Jennifer Lopez receiving a “first edition of the Iliad” from the male love interest in the 2015 film The Boy Next Door. Even though this is an actual 1884 Chicago edition of the Iliad, as translated by Alexander Pope, it has become an object of Pop Bibliography through context. “Real” is a difficult word to pin down sometimes.

The fabled “first edition of The Iliad,” as seen in The Boy Next Door.

Once you start looking for it, you see Pop Bibliography everywhere. But its existence is not to say that most people are getting books “wrong”; this is a descriptive concept, not a prescriptive one. Acknowledging the presence of Pop Bibliography content allows us to get a sense of how people outside the field conceptualize the past, and of how they understand book history in general. It is a chance for practitioners to connect with new audiences on their level, and to reflect on what their subjects of study mean to those audiences. It tells on us as much as it does the general zeitgeist; there is inherently a large element of autoethnography when confronting it, looking back on your own experiences with chimera books on screens or pages before you’d ever set foot in a reading room. Pop Bibliography is now a permanent part of the rare book landscape, and identifying it as such opens new doors for inquiry into the material culture of the book.

*I denounce in the strongest terms JK Rowling’s harmful, disgusting transphobia, but the Harry Potter series is one of the most prevalent sources of Pop Bibliography in the current media culture, and its influence must be acknowledged.

Works cited

Brian Cummings. “The Book as a Symbol,” in The Book: A Global History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Cornelius Holtorf. “The Presence of Pastness: Themed Environments and Beyond,” in Staging the Past. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2010.

Jessica Pressman. Bookishness. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.